Peter Lesley & Dr. RMS Jackson

Peter Lesley, Geologist

On April 1, 1858, Professor Peter Lesley and his friend and companion Dr. RMS Jackson encountered a host of Blairsville citizens attacking three slave catchers. Peter Lesley wrote to noted Abolitionist Theodore Parker on April 6th, 1858 about the event:

. Peter Lesley was a geologist and director of the second Geological Survey of Pennsylvania (1874-1896). He was also librarian (1858-1885), secretary (1859-1887), and vice president (1887-1898) of the American Philosophical Society.

When J. Peter Lesley (1819-1903) graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1838, he intended for the Presbyterian ministry, but when ill health intervened, he was set off on a path that would make him one of the most influential geologists in 19th century Pennsylvania. In order to help rebuild his strength and restore his health, Lesley accepted an appointment with the first Pennsylvania Geological Survey under the direction of Henry Darwin Rogers and engaged in structural and stratigraphic work and topographical and geological mapping in the Pennsylvania anthracite belt. By 1841, he had recovered sufficiently to return to his divinity studies at Princeton Theological Seminary but continued all the while to work for the Survey on a part time basis, mostly in preparing maps.

After a trip to Europe in 1844 to polish off his ministerial education, Lesley accepted a pulpit in rural central Pennsylvania, and moved three years later to take the helm of a Congregational church in Milton, Massachusetts. There he came into contact with a politically progressive, intellectually stimulating crowd that included Lydia Maria Child, James Freeman Clarke, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and the fringes of the Transcendentalists and reformers. A young Unitarian member of this circle, Susan Inches Lyman, became Lesley's wife in February, 1849, and both shared their associates' progressive political and social vision.

As he had all along, Lesley continued to work on an occasional basis for the Geological Survey until 1852, when a long-standing conflict with Rogers over credit for field assistants led him to resign. That year marked an even more profound change in Lesley's life, as he also decided to leave the church and return home to Pennsylvania. Coinciding with the period of extraordinary expansion in the coal and rail industries in Pennsylvania, Lesley devoted himself fully to geological work. Employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company and other corporations, Lesley was an important cartographer - one of the first to employ contour lines to represent topography - and was an important writer and synthesizer of knowledge about the coal and iron regions. He is credited with some of the first systematic studies of coal, oil, and gas resources in the state.

Lesley's rising prestige in scientific circles led to his election to the American Philosophical Society in 1856, where he instilled himself in the Society's leadership, serving as librarian (1858-1885), secretary (1859-1887), and vice president (1887-1898). During his tenure as librarian, he introduced a new system of arranging books by subject, anticipating in some ways Melvil Dewey's system, but employing small spine labels arranged in the colors of the spectrum to represent the areas of knowledge. He was, as well, a charter member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1863.

Lured to the University of Pennsylvania as Professor of Mining in 1859, Lesley became a fixture there, too. Lesley's acquisition of a major collection of fossils, rocks, and minerals from James Hall, state geologist of New York, helped consolidate geology as a major subject of study at Penn. Lesley later became Professor of Geology and Mining Engineering and Dean of the Science Faculty, and in 1875, he was appointed Dean of the newly formed Towne Scientific School.

The continuing importance of the oil industry to Pennsylvania's economy led to calls for a second state Geological Survey, and for the duration of its existence, from 1874 to 1889, Lesley served as Director. An immense operation by the standards of the first Survey, at least, the second Survey was also immensely productive, issuing dozens of publications on the topography, geology, paleontology, and mineral resources of the state. He was in the midst of preparing a state-mandated final report for the Survey in 1893 when he suffered a complete breakdown. He never recovered.

Lesley died in 1903. One of his two daughters, Mary, married the prominent Minneapolis businessman, Charles W. Ames (1855-1921), and the other, Margaret Lesley Bush-Brown (1857-1944), became a well known artist, some of whose portraits hang in the APS.

From the guide to the J.P. Lesley Papers, 1826-1898, (American Philosophical Society)

Dr. RMS Jackson was a physician born in Alexandria, Pennsylvania on April 20, 1815. A graduate of Jefferson Medical College in 1838, he opened a practice in Blairsville, PA in 1842. After 10 years in Blairsville moved his practice to Cresson, Pennsylvania, where he operated medicine for several years in his Allegheny Mountain Health Institute. Jackson was known for his scientific attainments, especially as a botanist and geologist.

In 1856 following the attack by Sen Brooks of South Carolina, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner sought refuge and recovery at the Allegheny Mountain Institute under Jackson’s care.

On April 20, 1861, Jackson was commissioned as a medical surgeon with the 3rd Pennsylvania Infantry. While working in service to the Union Army, Jackson’s wife died. By February 1863, Jackson was appointed surgeon with the PA 11th volunteers and in 1864 medical inspector of the 23d army corps and acting medical director of the Department of the Ohio. He was a member of the Pennsylvania geological commission, of the American philosophical society, and other learned bodies. Dr. Jackson was an enthusiastic mountaineer, and published a work entitled "The Mountain". Dr. RMS Jackson died on pneumonia at Lookout Hospital in Chattanooga, Tennessee, January 28th, 1865.

CHARLES SUMNER, DOCTOR JACKSON, AND THE MOUNTAIN

By RONALD L. FILIPPELLI*

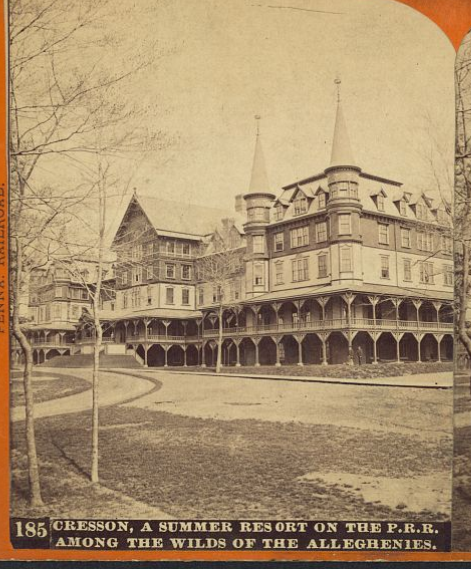

ON AUGUST 3, 1856, Senator Charles Sumner arrived at the top of Cresson Mountain, in the wilds of the Pennsylvania Alleghenies. It was the most recent stop on an odyssey which had begun for the Massachusetts senator with his brutal caning by Preston Books of South Carolina on May 22 in the senate chamber.' As Sumner stepped from the Pennsylvania Railroad car in the company of his friend, the Reverend William Henry Furness of Philadelphia, he was greeted by the physician who was to be responsible for his care during the month of August. During that time Sumner, the powerful abolitionist from Massachusetts, and his country doctor, a loyal Democratic postmaster from Cresson, Pennsylvania, developed a relationship which provides us with a delightful account of a friendship between two extraordinary men and also sheds further light on the controversial convalescence of Charles Sumner.

Senator Preston Brooks

Senator Charles Sumner

Dr. Robert Montgomery Smith Jackson was born in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania, on April 20, 1815, the son of a Presbyterian minister from Ireland. Before the child reached three years of age, both his parents had died. Details of his boyhood are scarce, but in 1836 young Jackson graduated from Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. He immediately enrolled as a medical student at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, from which he graduated in 1838. At that point Jackson decided to indulge another great passion of his life, geology. As a boy in western Pennsylvania he developed a love for nature which bordered on the transcendental mysticism of the Concord group. When an opportunity presented itself to acquire a political appointment as assistant state geologist, he readily accepted. He held the position for four years, much of which he spent in the field. During those winters he returned to Philadelphia, where he performed a kind of medical internship in the public institutions of the city. In his spare time he pursued avid interests in science and literature. By 1843, Jackson had apparently decided to devote his primary energies to the practice of medicine, and he set out to find a home somewhere in western Pennsylvania. Armed with numerous letters of introduction from physicians in Philadelphia and elsewhere, he finally settled in the small community of Blairsville in Indiana County. No doubt of considerable importance in his decision to settle down to medicine was the fact that he had recently married. His bride, Mary Herron of Uniontown, Pennsylvania, the niece of Andrew "tariff Andy" Stewart and great-granddaughter of the early Pennsylvania ironmaster, Andrew Oliphant, undoubtedly preferred the settled life of a country doctor's wife to that of companion to a roving geologist. Jackson's ambition had always been to combine his medical practice with enjoyment of the bounties of nature. The wilds of the Alleghenies surrounding Blairsville provided the perfect setting. He envisioned a health spa located adjacent to some of western Pennsylvania's most famous health springs. Out of this dream emerged the Allegheny Mountain Health Institute. Incorporated in 1854, it was located at the "Allegheny Springs," Cresson Station, 243 miles from Philadelphia and 101 miles from Pittsburgh at the summit of the mountain, 2300 feet above sea level.' In a more poetic vein, a promotion probably written by Dr. Jackson placed it "on the eastern rim of the great interior continental basis . . . in the line of temperate latitude, and above the plane of perpetual malaria." The seeker of pleasure and luxury was promised "all he could desire," including "unobjectionable cuisine, a 'cool, delightful climate, and every amusement desirable." For the sufferer from ennui, heat, disease, or for invalids, the institute offered "absolute comfort and relief for the time being and certain prolongation of life- in the future." It was as an invalid rather than a seeker of pleasure that Charles Sumner arrived at "the Mountain," Jackson's name for the institute. He came in a hopeful mood, cautiously sensing that he was recovering, but wary because previous spells of optimism had been followed 'by setbacks. The sight which greeted him as he stepped from the train in the peaceful Alleghenies must have pleased the weary Sumner. A broad expanse of lawn led up to two large hotel buildings surrounded 'by shade trees. Unfortunately, the senator's enjoyment of the restful vista was probably impeded by his condition upon arrival. The long train ride must have tired him considerably. Jackson noted that his new patient appeared "extremely unwell." Jackson examined Sumner almost immediately. He had not been given a medical report by any of the previous physicians on the case. His examination revealed a "watery condition" of the blood accompanied by a "general pallor of countenance and flabbiness of solids." On the surface of the head he found a "slight redness around the cicatrices of the recently healed cuts" as well as some "morbid sensitivity on pressure." When he walked the senator tottered as if partially paralyzed. The slightest exertion exhausted him and often produced severe headaches. Jackson felt that the symptoms pointed to the "head and spine as the area of a highly morbid condition." The brain and spinal cord appeared to have been afflicted with a formidable lesion.' He believed that Sumner had suffered from a "great general disarrangement, local disease, or threatening organic attavation of some important tissue or organ." Jackson's florid diagnosis revealed that he was very much a medical man of his time. One thing was certain; however, Sumner was a very sick man and in Jackson's opinion, the outcome remained in doubt.' The senator was not without aids with which to wage the struggle. His happily married physician somewhat humorously noted that while the fact that Sumner was a bachelor was critical, it was of no consequence to the case. He found his patient a six-foot two inch muscular man of nervous temperament in the "full zenith of manhood."'' The doctor's prescription combined the influences of his medical training with a geologist's belief in the healing powers of nature. Sumner was to be subjected to a "judicious diet, mild tonic agents, constant exercise in the air, on horseback, or in a carriage," accompanied by a cessation of "all active efforts of diseased parts." This was to result in a gradual "stringing up and intonation of the whole body under the influence of mountain air, mountain water and change of climate."' Apparently wishing to avoid the publicity of a public hotel at the resort, Sumner took lodgings with the Jackson family. The arrangement evidently proved to be highly satisfactory. Sumner enjoyed the atmosphere of the doctor's home, especially the attention of the Jackson women. He affectionately referred to Cary, the doctor's daughter, as "the lady with the bright eyes," and to Mrs Jackson as "the lady with the soft voice."' The soft voice may well have been employed to chide Sumner about his moderate drinking, since Mrs. Jackson was a teetotaler. It is also interesting to speculate on the conversations which took place during the August evenings between two such articulate and interesting companions. One must, however, feel some sympathy for the ladies in the presence of two such verbose men. One thing is certain; at some point during the month, Jackson, hitherto a minor political functionary in the Buchanan organization, became an ardent Sumner partisan.

The doctor came to feel that Sumner was nothing less than "one who seems by fate to have been consecrated to the progress and well-being of his race."- While the senator apparently found a measure of peace at the Mountain, his physical and mental condition remained in a state of flux. The most alarming sign of his infirmity continued to be the difficulty he had walking. Before the assault Sumner had been a strong walker. He considered ten- or twelve-mile hikes to be no more than "pleasant exercise." While at the Mountain, however, his gait appeared to be that of a much older man. One observer compared it to "the kind of steps one takes when creeping through a darkened chamber under the at some point during the month, Jackson, hitherto a minor political functionary in the Buchanan organization, became an ardent Sumner partisan. The doctor came to feel that Sumner was nothing less than "one who seems by fate to have been consecrated to the progress and well-being of his race."- While the senator apparently found a measure of peace at the Mountain, his physical and mental condition remained in a state of flux. The most alarming sign of his infirmity continued to be the difficulty he had walking. Before the assault Sumner had been a strong walker. He considered ten- or twelve-mile hikes to be no more than "pleasant exercise." While at the Mountain, however, his gait appeared to be that of a much older man. One observer compared it to "the kind of steps one takes when creeping through a darkened chamber under the influence of a paroxysm of nervous headache. ...

" Whatever his physical condition, he frequently told visitors that he would return to Washington in two weeks. He wrote Joshua Giddings that he longed to return to the senate to expose the "brutality of the slave oligarchy."" These were brave words for a man who was driven to the sofa after reading or writing only ten or so letters a day. While the Institute was remote, its location on the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad made it reasonably accessible. Anson Burlingame, and Mrs. Jane Swisshelm visited the Mountain to see the condition of their hero for themselves. Theodore Parker also planned to visit, but 'he was misinformed that Sumner had left Cresson. Parker thanked Dr. Jackson for helping "this noble man." These visits were often occasions of considerable pleasure to the patient. On one, Burlingame, the Massachusetts Congressman who gained a measure of notoriety by challenging Brooks to a duel to avenge Sumner, arrived at the Mountain in the company of a gentleman and a lady. Along with Dr. Jackson, the party engaged in lengthy -conversations and frequent rides into the lush mountains. Oddly enough, while walking proved difficult, Sumner han no difficulty sitting a horse. By mid-August riding had apparently become his most enjoyable daily exercise. In any event, the company of the Burlingame party proved so enjoyable that Dr. Jackson practically had to force Sumner to retire for the evening.- Letters from friends also acted as a stimulant. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that even though he "grieved" that Massachusetts would be crippled in the Senate, he believed that the senator's suffering had been a "stranger manifest benefit to the country." Apparently referring to the use to which Sumner's political friends were putting his martyrdom, Emerson noted that, "Bad times are bitter when passing; but, if well used, how glorious forever afterward." Emerson also sent his regards to Dr. Jackson. A letter from Charles Francis Adams assured the senator that his handwriting indicated he was gaining strength and would soon be himself again. Whatever the real state of Sumner's health and attitude-and it fluctuated from day to day-they were objects of lively national interest. Brooks' assault had become the focal point of the sectional struggle, and the question of Sumner's health was pursued with great interest by both sides. Sumner's opponents, the South, and the Buchanan Democrats saw the senator using his martyrdom to enhance the anti-slavery position. Sumner was not ill, but hiding in the Pennsylvania mountains, they claimed. Sumner's supporters, on the other hand, pointed to his broken health as proof of the inhumanity of the pro-slavery forces. The isolation of Cresson provided the distance necessary for rumor and speculation to flourish. Sumner's friends sometimes seemed to want him to be ill in order to suit their need for him to remain a martyr, at least until the hotly contested presidential election took place. Theodore Parker gloomily wrote that the senator's condition was critical. "I have never thought he would recover," wrote Parker.Y Williamn Seward was even more dramatic. He had "Sumner .. . contending with death in the mountains of Pennsylvania." One less emotional Sumner confidant wrote the senator of the difficulty of finding "'authentic" accounts of his health. The anti-slavery press contributed to the confusion by printing a plethora of "eye witness" accounts of Sumner's health, some of them contradictory. In the same issue of the Anti-Slavery Standard appeared, "Neither sea air nor mountain air has yet produced any effect . . . Mr. Sumner continues in a state of prostration"; and ". . . Sumner today . . . announces his health is improving . . . [and] . . . expresses the greatest anxiety to take his seat before the adjournment and may do so." A Philadelphia physician and clergyman reported that the "healing breath of the Alleghenies" was working to good effect on Sumner.